The Special Meter 2: 'Ollie the Magic Bum' and Skateboarding's Portrayal Problem

Skate videos have a history of featuring people experiencing homelessness, mental illness, substance abuse or all of the above, often as comic relief – or even props.

Welcome to the second edition of The Special Meter, a series about the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater video game series. (To read the first one, click here.)

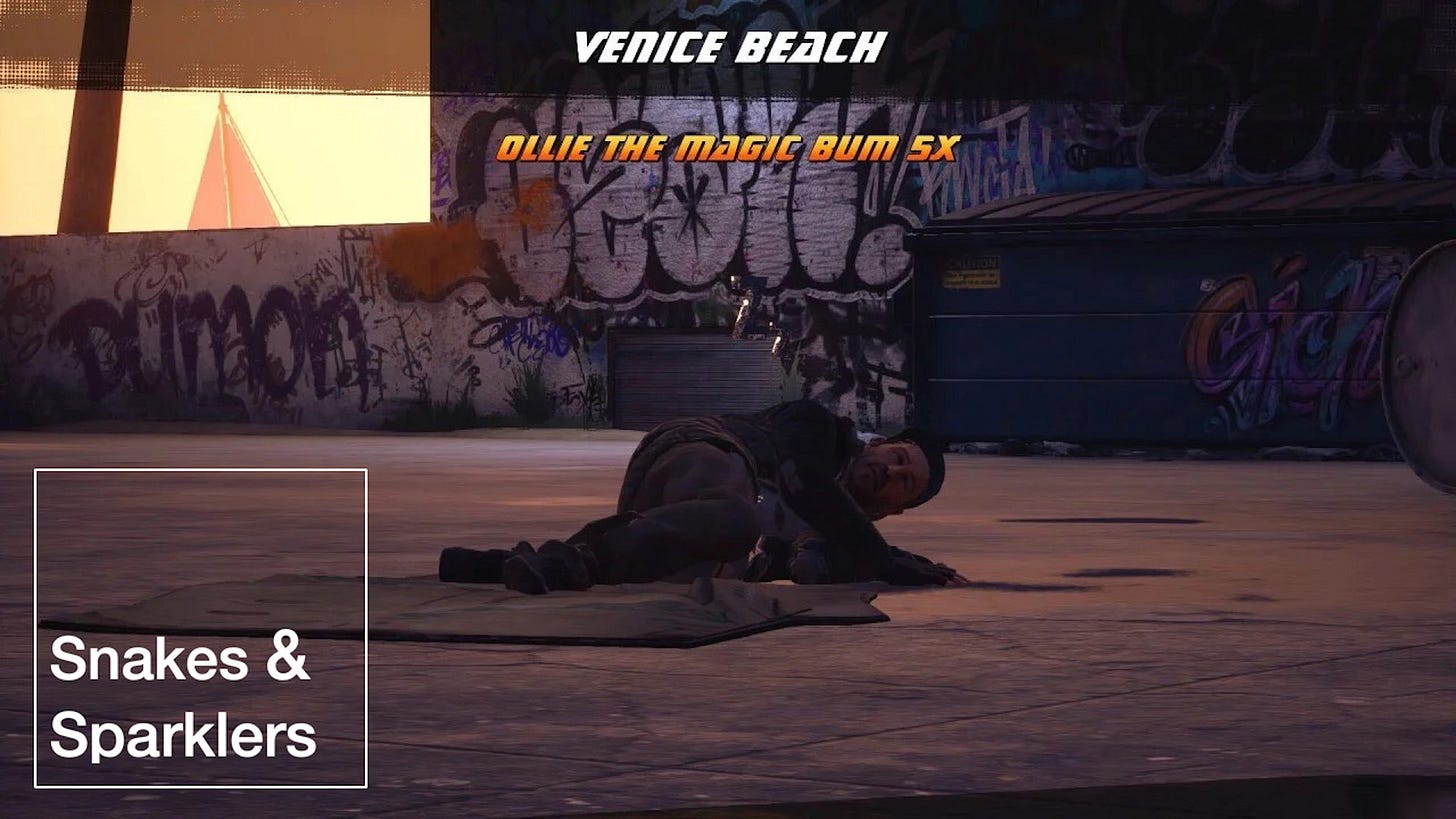

This week, I’m on Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2, which introduced the “Ollie the Magic Bum” challenge, where you have to ollie over a homeless person in various spots around the Venice Beach level. The character, Ollie, and the challenge, continued into future games. And even though the game came out 24 years ago, the issue here continues to this day in skateboarding media.

This is an article I had actually pitched to Jeremy Gordon from The Outline right before the pandemic and, unfortunately, the end of The Outline. It eventually found a new life in Secret, a magazine by then-Mic staffer Jeff Ihaza, but it never got a real wide release beyond New York City and a quiet online publication.

Four years and an inaugural Olympics for skateboarding later, the practice of using people in and on the streets, especially those who are homeless, or possibly experiencing mental health or addiction issues, is still prevalent in skateboarding. I asked some prominent, long-time skateboard filmers and documentarians like Jason Hernandez and Patrick O’Dell, as well as a professor of media studies at Temple University, about this portrayal, why skateboarding is still lagging behind other subcultures in a way, and drawing a line between artistic expression and documentarianism and dehumanization. I also made some minor tweaks to the article to make it more current.

If you’ve ever watched a skate video, basically from their inception to the rapid-fire YouTube release schedule of today, you’ve likely encountered a clip featuring someone experiencing homelessness. At its most harmless, skate videos portray them as excited onlookers near the session. However, the line between celebration and exploitation is never terribly clear. As skateboarding, along with the world at large, reconsiders its relationship to privilege, white supremacy, and mental health, it seems like as good a time as ever to reconsider how skateboarding captures the world around them.

“A normal businessperson might walk by a homeless person and walk around, you know, like purposely walk away from them because they might be scared of them or whatever,” says Jason Hernandez, who has been filming skateboarding for about 20 years for companies like Birdhouse Skateboards. “Or, they think that they’re gross or something. Skateboarders, we really are in the streets all the time.”

Skateboarders and people who are homeless exist in a similar world. Both groups use public space for unintended purposes, much to the displeasure of security guards — another group who frequently star in videos unwillingly.

Skate footage often takes a documentarian approach. An hours-long battle with a specific trick might find a skater encountering a number of passersby who typically go unnoticed. It’s not uncommon, in a quest for a certain “raw” aesthetic, for skate videos to highlight the homeless as a means of broadcasting an unfiltered take on city life.

“I think that’s just the nature of the urban landscape,” says Patrick O’Dell, whose documentary series Epicly Later’d profiles major skateboarding figures. “There’s going to be homeless people around. And I don’t think a lot of it is necessarily nefarious on the part of the skaters. That’s just how skating is. I’ve always been in favor of honesty. But there have been times in videos when I’ve seen things that kind of bummed me out.”

Take, for example, a clip from the seminal skate video Baker 3, which came out in 2005. At the introduction of Antuan Dixon’s part, a woman undergoing what looks like a mental health crisis is shown screaming in the street. The camera is placed on a ledge in such a way that suggests she is being filmed without her consent. Then the camera turns to Dixon who looks bemused by the interaction and describes the woman as crazy. It’s casual, and typically slips under the radar in a singular skate video, but when considered holistically, raises questions about what certain clips might mean for different viewers.

“For a lot of people, the media are their only access to these marginalized groups,” says Dr. Lauren Kogen, a professor of media studies at Temple University, whose work focuses on the depiction of disenfranchised groups. “It’s not part of their lives. So, if the media is their only representation of homelessness, then they believe that’s the whole picture.”

And when impressionable viewers (who now have phones in their pockets with video capabilities far beyond what the skaters of the ‘90s and ‘00s had, as well as the ability to instantly publish to the masses) go out to make their own skate videos, they rely on the tropes they’ve seen from the pros, and the pattern continues. I know, because I was once an impressionable kid making videos. A lot of kids (and adults) just aren’t creative enough to avoid copying harmful tropes.

There was a post on the SLAP message board, a platform built for discussing skate culture and sharing clips that is often full of vocabulary that we’d now generously call “antiquated,” plainly asking people to post “some of your favorite clips of skaters robbing these lost souls of their last shred of human dignity by treating them as an inanimate object?”

The original poster shared a 2014 GX1000 video in which someone did a trick over someone laying on the sidewalk.

He was right about one thing, unfortunately: Featuring marginalized people has been a time honored tradition to an extent.

A 2014 video from LurkNYC showed someone ollying at high speed over another guy on the sidewalk (longways, i.e. more dangerous and going high-speed at the guy’s head).

A 2010 edit from the skate company Krooked showed something similar.

It’s even a joke on “South Park,” where Cartman bets how many people he can jump over on his skateboard.

“Some of the homeless populations that I’ve worked with in Philadelphia self-medicate in part because they’re traumatized,” Kogen continued. “As a filmmaker, one needs to recognize what their images add to that narrative. So, even if they just say, ‘Well, I didn’t explicitly say that homeless people are generally this way. I’m not talking about what the causes are,’ that doesn’t mean that you’re not sending a message to audiences about what these people are like and why they are that way. I definitely think the onus falls on the filmmakers to be a little more aware of the messages that they’re sending out there.”

O’Dell points to an overall reluctance from skateboarders to be self-critical.

“I’ve encountered that a lot. Skateboarding in the past has had a lot of issues,” he said.

The identity of skateboarding is rooted in a belief in a pure form of self-expression, free from rules and regulations and governing bodies — i.e. people telling you no. When a group’s identity is built around such an ironclad ethos of doing whatever you want, how do you take hard looks in a mirror?

Skateboarding is an Olympic sport — a logical stop in its roll toward corporatization that started in the ‘70s and continued through the X-Games and Tony Hawk video games. Now that it’s now on a playing field with “traditional” sports, there’s an increased possibility of outside scrutiny that could cause skateboarding to self-correct. But O’Dell thinks such input can only go so far.

“I think people might look at things that have happened in skating more closely,” he says. “In baseball, if there’s domestic violence or something happening, they’ll eject that person from the sport. There’s nothing like that in skating. If there was domestic violence in skating, it would have to be up to the company or up to the consumer.”

It’s similar to something like the music scene, where it’s up to the consumer and the fan to speak up if someone has exhibited behavior deemed harmful to the community, and choose not to engage with that artist by buying music or concert tickets. (Notice the lack of the word “cancel.”)

There are no governing bodies in skateboarding the way there are in other sports. The closest things, perhaps, are the corporations like Nike and Adidas — now pillars of the skate world — that could smooth over some of the sport’s rough edges more willingly than the “core” skate brands. But, historically, they seem to have spent more time questioning and nitpicking other artistic decisions, the way anyone who has worked in fields like advertising will tell you their corporate clients tend to do.

“Working at Nike, it actually sort of desensitized me to randomness, if you will,” Hernandez said. “It was almost pointless to explain to someone in legal who knows literally nothing about skateboarding about why artistically I chose to show this guy filming pigeons in the park. Half of the time, I’d have to change the shot. I stopped shooting certain things.”

But for every brand like Nike that wants a clean-cut, consumer-friendly image in skateboarding, there are brands that want to do things their way, optics be damned. Brands and filmers are still going “hijinx,” common vernacular for anything from skaters joking around between tricks to yelling at a person walking with their groceries, in videos. That “hijinx” clip might also be of a mentally ill person living in the streets, heavy drinking or casual racism.

Sometimes it’s not even casual. To revisit Baker 3, the very intro of the whole video shows some of the skaters following and mocking an Asian woman. The video title appears while she looks at them, upset, and their verbal assault fades out with the audio.

“When I grew up, skateboarding was this raw thing you did, and it was a fuck-you to everybody except skaters,” Hernandez says. “Honestly, it’s kind of annoying. I wish the younger me would’ve been smarter. ... You don’t need it, you know? You don’t need that stuff in your videos to make your video better.”

Similarly, O’Dell points to his own maturity as a factor in his opinion shift.

“There are a lot of things I see in videos that I think, ‘Oh, this sends a bad message,’ but I’m 40-something-years-old, so my opinion on what’s a bad message has also changed over time, too,” he said. “When I watched videos when I was 19 or something, I thought things were pretty cool, but now I wouldn’t watch it.”

O’Dell points out how skateboarding as a whole has learned certain lessons and drawn boundaries. Things like upskirt shots probably weren’t uncommon in the ‘90s, but that filmers today would never dream of including such footage in a skate video, and rightfully so. But such belated progress is hardly a reason for celebration, O’Dell says.

“Skaters really want to self-congratulate over any sort of progress that’s been made, but not really take any deep dives,” O’Dell says. “Like any activity, there’s a ton of shithead skaters and there’s a ton of cool skaters.”

One obvious step toward change is to treat people like people. Including people on their terms is a lot more reasonable than throwing something at a person minding their own business or, worse, kickflipping over someone staying warm on a heating vent. It’s something O’Dell thinks of as kind of a no-brainer now.

“I remember I took a picture of a homeless guy and he got mad at me,” he says. “It seemed to be this wake-up call to me, like, I can’t just go up, even though I like shooting street photos and sometimes there’s a point you’re not always getting permission, it’s not my right to shoot photos of whoever I want, you know?”

“If there’s anybody out there who’s making a skate video, it’s your vision. You can do whatever you want,” Hernandez says. “You can make whatever you want. That’s the beauty of editing and shooting and making something. But sometimes you definitely don’t need to have something in there that’s going to potentially harm someone even more than they’re already feeling or already are. Not that any of these homeless people are going to watch themselves in a skateboard film. But do you need it? Probably not.”

This isn’t all to say that every time these people are on skate footage they’re the butt of a joke. But they often are. And until skateboarding as a whole treats the practice as harmful, rather than just another facet of the culture, it will cause real harm by essentially telling people that all homeless people are dangerous, “crazy,” or props to use for entertainment.

“So, if instead of showing the homeless people as being silly or someone to laugh at – drunk, aggressive – instead of you show them as regular people who have personalities who laugh, who are kind, who have fun, then that’s the image you are putting forth as homeless people,” Kogen says. “And that’s the image people get, and that’s a completely different story.”

Skateboarding will probably never have a true centralized governing body like other sports. And, as someone from the skateboarding world, it shouldn’t. It brings back the debate of whether skateboarding is a sport at all, or whether it’s an artform. If you lean more toward the art form argument, then you understand that art is there to be criticized. And, for a long time, the art of the skateboard video was perhaps criticized for the wrong things.

For the record, that screengrab at the top of Ollie the Magic Bum is from the 2021 remaster of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2.

Today’s Snakes and Sparklers musical guest is Been Stellar

Bonus for those who scrolled down: THPS2 included a Philadelphia level, which was a rough recreation of LOVE Park and the surrounding area, and FDR (located miles away in real life). The most accurate part was the bus that can and will hit you.

When the city was about to renovate LOVE Park (making it much less skater-friendly), they finally eased up the security to give skaters a few days to finally skate the ledges without getting hassled by the cops (but still had to deal with out-of-towners trying to skate the fountain gap and ruining it for everyone else). I took my camera down there on a very cold February day, and here are some of my favorite pictures from it: